Sarcoma

What is sarcoma?

The Australia and New Zealand Sarcoma Association (ANZSA), Australia’s peak scientific body for sarcoma research, defines sarcoma as: A rare and complex cancer of the bone, cartilage or soft tissues such as fat, muscle, connective tissue or blood vessels.

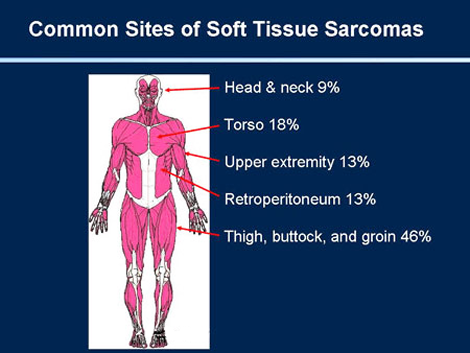

Sarcomas can form anywhere in the body, are frequently hidden deep in the limbs. and are often misdiagnosed as a benign (non-cancerous) lump, or as a sporting injury or growing pains in young people.

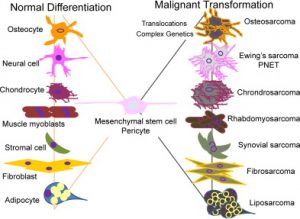

There are more than 150 subtypes of sarcoma, many of which have distinct clinical characteristics with unique natural history and tumour biology.

These can be grouped into two major types – soft tissue and bone.

SOFT TISSUE SARCOMAS

Soft Tissue Sarcomas are a rare form of cancer. Due to their rarity, it is crucial for patients to seek a sarcoma cancer specialist and multi -disciplinary team for treatment. Soft tissue sarcoma can occur in the muscles, fat, blood vessels, tendons, fibrous tissues and synovial tissues (tissues around joints). Soft tissue sarcomas can invade surrounding tissue and can metastasise (spread) to other organs of the body forming a secondary tumour. Secondary tumours are referred to as metastatic soft tissue sarcoma because they are part of the original cancer and are not a new disease. Non- cancerous soft tissue tumours are benign and are rarely life threatening.

Symptoms

Soft tissue sarcomas often have no symptoms in the early stages but can cause symptoms as they grow larger or spread. The symptoms depend on where the cancer develops. You should see your GP if you have a worrying lump, particularly one that is getting bigger over time, or is the size of a golf ball or larger.

Diagnosis

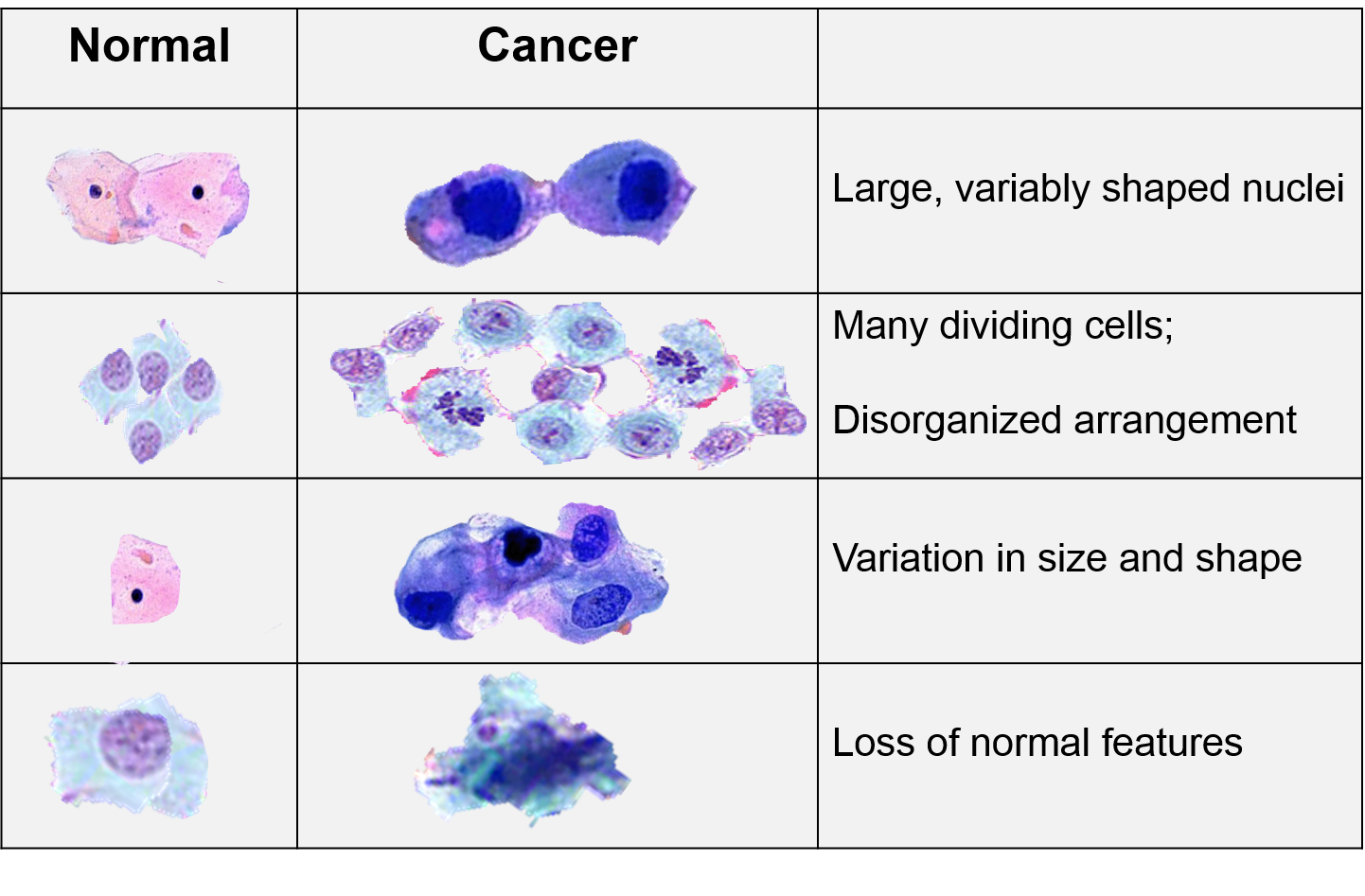

Soft tissue sarcomas can only be diagnosed by a surgical biopsy, which is a procedure which removes tissue from the tumour so that it can be analysed under a microscope.

Treatment

Soft tissue sarcomas are currently treated using surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Clinical trials are also testing the efficacy of immunotherapy and targeted therapies in combination with mainstream methods. Depending on the size, location, extent, and grade (growth rate) of the tumour, a combination of all or some of these treatments may be used. Biological therapy, such as treatment to stimulate the body’s immune system to fight cancer, or molecules that target certain genes expressed by the cancer cells, are also being used for some sarcomas.

*Treatment options should always be discussed with your oncologist and medical team.

BONE SARCOMAS

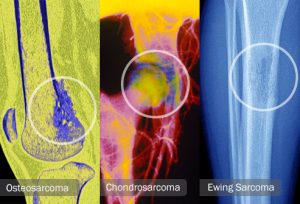

Bone sarcomas (bone cancers) are the second large group of sarcoma. There are three types of bone sarcoma: osteosarcoma; Ewing’s sarcoma; and chrondrosarcoma. Bone sarcomas are very likely to be diagnosed in children, and due to the rarity and severity of bone cancer, a bone cancer specialist such as an orthopaedic oncologist, together with a multidisciplinary team, should be consulted in the treatment of the disease.

Bone tumours can be benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Benign bone tumours are rarely life threatening and do not spread within the body, however, they can grow and compress healthy bone tissue.

The most common type of primary bone cancer is osteosarcoma. Because it occurs in growing bones, it is most often found in children. Another type of primary bone cancer is chondrosarcoma which is found in the cartilage. This cancer occurs more often in adults. Ewing’s sarcoma can occur as either a bone sarcoma or a soft tissue sarcoma depending upon the original location in the tumour.Symptoms and signs

Symptoms

The signs of sarcoma depend on the site where they arise. Patients with bone sarcoma may present with the following symptoms:

- Bone swelling and pain which tends to worsen at night

- Fractures may develop after minor trauma as the bone is weakened by the tumour

- A new lump that may not necessarily be painful located anywhere in the body that increases in size, and may grow to a large size over time (patients experiencing soft tissue sarcomas)

- Problems with movement such as an unexplained limp

- Loss of feeling in the affected limb

- Unexplained weightloss and fatigue

Diagnosis

X-rays are used to locate a tumour, and if the x-ray suggests a tumour is present than a doctor may require further testing such as a CT scan, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or PET scan. Finally, a biopsy must be performed to determine if cancer is present, and is a procedure used to remove sample tissue from the tumour.

A surgeon, usually an orthopaedic oncologist, performs the procedure using a needle or making an incision. During a needle biopsy the surgeon makes a small hole in the bone and removes sample tissue with a small instrument. During an incisional biopsy, the surgeon cuts into the tumour and removes sample tissue. A Pathologist will then study the cells and tissues under a microscope to determine whether the tumour is cancerous.

The treatment of bone cancer depends on the size, location, type and stage of the cancer. Chemotherapy with surgery is often the primary treatment. While amputation of a limb is sometimes necessary, using chemotherapy either before or after surgery has allowed doctors to salvage the limb and improve survival in many cases. Radiation and immunotherapy, and targeted therapies may also present as treatment options.

Why are sarcomas dangerous?

They are hard to diagnose, hard to detect and hard to treat. Biopsy is the only diagnostic tool and surgery often the only curative treatment. Many sarcomas resist current cancer treatments.

Why multi-disciplinary care is important in sarcomas ?

There is evidence to support treatment by a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) for the treatment of sarcoma, can lead to more favourable survival outcomes.

An MDT would include:

A specialist sarcoma pathologist and/or radiologist who is able to review each patient’s pathology and radiology

A surgeon who is a member of a sarcoma MDT or a surgeon with tumour site-specific or age-appropriate skills, in consultation with the sarcoma MDT

Medical and radiation oncology expertise. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy should be carried out by appropriate specialists as recommended by a sarcoma MDT

Dedicated ancillary supportive care, which includes nursing, physio- and occupational therapy, age-appropriate psychosocial support and palliative care

Before you seek a second opinion, here are a few questions and points to consider:

Are you already being managed at a sarcoma service equipped with a multidisciplinary team?

If your answer is YES, your treating team may already be aware of other treatment options that are available in Australia and beyond. Sarcoma specialists in Australia and New Zealand are often well connected with international sarcoma experts. It is important that you ask as many questions as possible to your treating team who has all the information regarding your diagnosis (e.g. films, biopsy results).

Have you spoken to your GP?

It often helps to speak to your own GP, who knows you best. He/she may help you come up with more relevant questions that you should bring up with your treating team before making any decision.

Have you spoken to a sarcoma nurse?

Being diagnosed with a cancer can be overwhelming, especially if it is a rare cancer with limited information. Make sure you ask for a nurse who could provide you with additional support. Some treating centres may offer psychology or counselling support on site.

Are you unwell from your sarcoma and in need of urgent treatment?

If you are unwell from underlying sarcoma, it is probably in your best interest to commence the recommended treatment as soon as possible without much delay.

Seeking a second opinion

It is okay to ask for a second opinion and it is important that all your questions are addressed before you make an informed decision.

A second opinion can:

Confirm or clarify your doctor’s recommendations.

Help you to consider all the advantages and disadvantages of being on the clinical trial.

Assure you of the diagnosis of your sarcoma and the treatment advice given by your doctor.

Help you to be more informed, involved and engaged in your care and treatment.

It is important however, to keep in mind that seeking a second opinion often takes time – not just for an appointment to be made but also for the other sarcoma service to thoroughly review your case with scans and pathology, which can take several weeks to complete.

TREATMENT OPTIONS SHOULD ALWAYS BE DISCUSSED WITH YOUR ONCOLOGIST AND MEDICAL TEAM

*A DOCTOR SHOULD BE CONSULTED IF THE ABOVE SYMPTOMS OCCUR

*EARLY DIAGNOSIS MAY MEASURABLY IMPROVE SURVIVAL OUTCOMES

*DO NOT IGNORE SYMPTOMS WHICH DO NOT ABATE.

References

1. ANZSA – https://sarcoma.org.au/pages/about-sarcoma

2. Cancer Council Victoria – https://www.cancervic.org.au/cancer-information/types-of-cancer/soft_tissue_cancers/soft-tissue-cancers-overview.html

3. Kick Sarcoma – https://kicksarcoma.org.sg/what-are-sarcomas/types-of-sarcomas/

4. NHS – https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/soft-tissue-sarcoma/

5. Mayo Clinic – https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/soft-tissue-sarcoma/symptoms-causes/syc-20377725

6. The Liddy Shriver Sarcoma Initiative – http://sarcomahelp.org/sarcoma-treatment.html#tpm1_3

7. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare – https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia/contents/survival